“Who borrows the Medusa’s eye

Resigns to the empirical lie

The knower petrifies the known:

The subtle dancer turns to stone.” [1]

We begin our analysis by focusing on two key words in the opening line. “The movie will begin in five moments. The mindless voice announced.” The words moments and mindless. Why moments? It’s an odd choice that invokes a tension between the words minutes and moments. The notion of a movie beginning in five minutes, a much more standard usage in the English language. The choice of moment therefore serving as a linguistic provocation. Why not minutes? Perhaps in order to provoke a comparison between a minute and a moment. These synonymous terms both signify a short duration of time. The key difference between them is that the former emphasizes a quantitative aspect, whereas the latter emphasizes a qualitative aspect. Five minutes is always five minutes, 300 seconds, etc., but five moments could very well be five important milestones of a life, the moment of “birth your life and death” for example, as the poem continues further on. It’s not precise to measure time quantitatively in regards to “moments,” “five moments,” and yet this is how the “mindless voice” proceeds. Why?

It brings us to the use of mindless, to its connotation that aligns it more with the category of the quantitative, it implies a mechanical quality. The artificiality of the announcing voice that carries out its automatic function has an element of the routine, while there’s also another meaning to mindless, in fact, the more primary meaning of foolish or negligent, mind-numbing. “Mindless” as a quality of either the cause or effect of a mind-numbing process, the result or prerequisite of the automatic activity or indeed “entertainment,” as we are made aware of later on that the audience at The Movie will have “seen this entertainment through and through.”

“[They] appease us with images,” Morrison writes in “The Lords.”

“Through art they confuse us and blind us to our enslavement. Art adorns our prison walls, keeps us silent and diverted and indifferent.” This indifference is key.

The “entertainment” has become blasé. “[Y]our birth your life and death” that’s been seen “through and through” has too.

The audience files “languidly into the hall.” Languid means “lacking in vigor or vitality,” “lacking in spirit or interest,” “indifferent.” Everything about the process has an unsettling feeling of having become a routine, it’s as if going to the movies evolved into a ritual, in both senses of the word, as a routine but also as a religious ceremony. “The program,” “this entertainment,” The Movie is a modern ritual, a ceremony of mind-numbing effect that produces indifference in the viewer and saps them of their vitality.

“[A]s we seated and were darkened” is also interestingly phrased, “[we] were darkened” implies not only that the cinema hall, the room darkened but that the audience themselves “were darkened,” creating an analogous relationship between the individual hall and the individual members of the audience, the hall as macrocosm and the mind of the spectator as microcosm, as if the hall were a representation of the audience’s inner life. Indeed this classically oneiric metaphor recapitulates the age old homology between cinema and dreams. The Movie is a mass delusion or fantasy, a mechanical dream; it’s the quantification of moments and in a way, it’s a policing of the qualities of consciousness.

“Did you have a good world when you died? Enough to base a movie on?”

This line turned out to be eerily prophetic, like another vision of Morrison’s that came true in his anticipation of electronica music of the new millennium, in an interview with The Doors on PBS’s Critique show on April 28, 1969.

The new generation’s music will be, it’ll have a synthesis of [country and blues] and some third thing. It’ll be entirely, maybe it’ll be, it might rely heavily on electronics, tapes, I can kind of envision maybe one person with a lot of machines, tapes, and electronics set up, singing or speaking and using machines. [2]

“Did you have a good world when you died? Enough to base a movie on?” A movie based on Morrison’s life was produced sure enough in 1991, featuring this track, “The Movie” by The Doors, right in the opening scene no less. Ironically or according to fate, or the prescience of Morrison’s vision, the film famously gets him embarrassingly wrong, turning him into an awkward caricature. It is in its own ways mind-numbing and negligent, for example in misrepresenting aspects of the way that Morrison died by framing him as obsessed with death. It conjures up a maniacal dream image of a man who seemingly wanted to die, and whose death is hence no mystery but rather a blasé event, that “is not new,” for we’ve seen it “through and through.” And this is especially true in the wake of the many clichés and tropes of a musical biopic on the self-destructive rockstar, of which this film is in some sense a founding example.

“The Doors” movie does for Jim Morrison what The Movie does for its audience in his spoken word poem, to a degree it’s a policing of qualities in who this man was; what the factual details of his life were; and even in the final analysis, of what his life means. The sum total of a life gets reduced to a few moments of mind-numbing screen time, to “entertainment,” a “program.”

To be fair the 1991 movie “The Doors”—though a seminal event in shaping the image of Jim Morrison—is still part of a longer tradition that existed before the movie existed; the overemphasizing of the darker aspects of Morrison’s personality, through representational works is a tradition inaugurated with the 1980 publishing of his salacious “biography” No One Here Gets Out Alive. But the effect remains the same. Whether intentional or unintentional, conscious or not the effect results in a policing of qualities, although arguably any biography, representation or symbol is inevitably going to do this, precisely because any textual or symbolic representation of anything ever is always already doing this. We can never know anything or anyone completely through mere words or images, through a text or symbolic representation of any subject, alone. For “the map is not the territory,” (Alfred Korzybski). It’s never the territory, and yet this is the mania of the Emperor, “[described by Jorge Luis Borges] who wanted to have such an exact map of the empire that he would have to go back over his territory at all its points and bring it up to scale, so much so that the monarch’s subjects spent as much time and energy detailing it and maintaining it that the empire ‘itself’ fell into ruins,” (Jean-Francois Lyotard, Libidinal Economy, 1973).

I’m getting out of here. Where are you going? To the other side of morning. [3]

This is where the thrust of the poem shifts, “the best part of the trip” (The Soft Parade, 1969) or more like the moment of freak-out. It’s as if one of the spectators in the audience experiences a bad acid flashback or a rotten sense of déjà vu, there’s something uncanny going on. “Where are you going?”

The question comes on like a voice in his head, from that same announcing “mindless voice” from earlier, but now in the theater of the individual’s mind. Microcosmic, it speaks directly to him, responding to his actions or his fear, the desire to run, and so it must be hallucinated and not actually experienced in the macrocosmic hall, experienced as a real illusion on the screen. Or perhaps it could be; what exactly is the difference between a real and a fake fantasy? “Where are you going? To the other side of morning.”

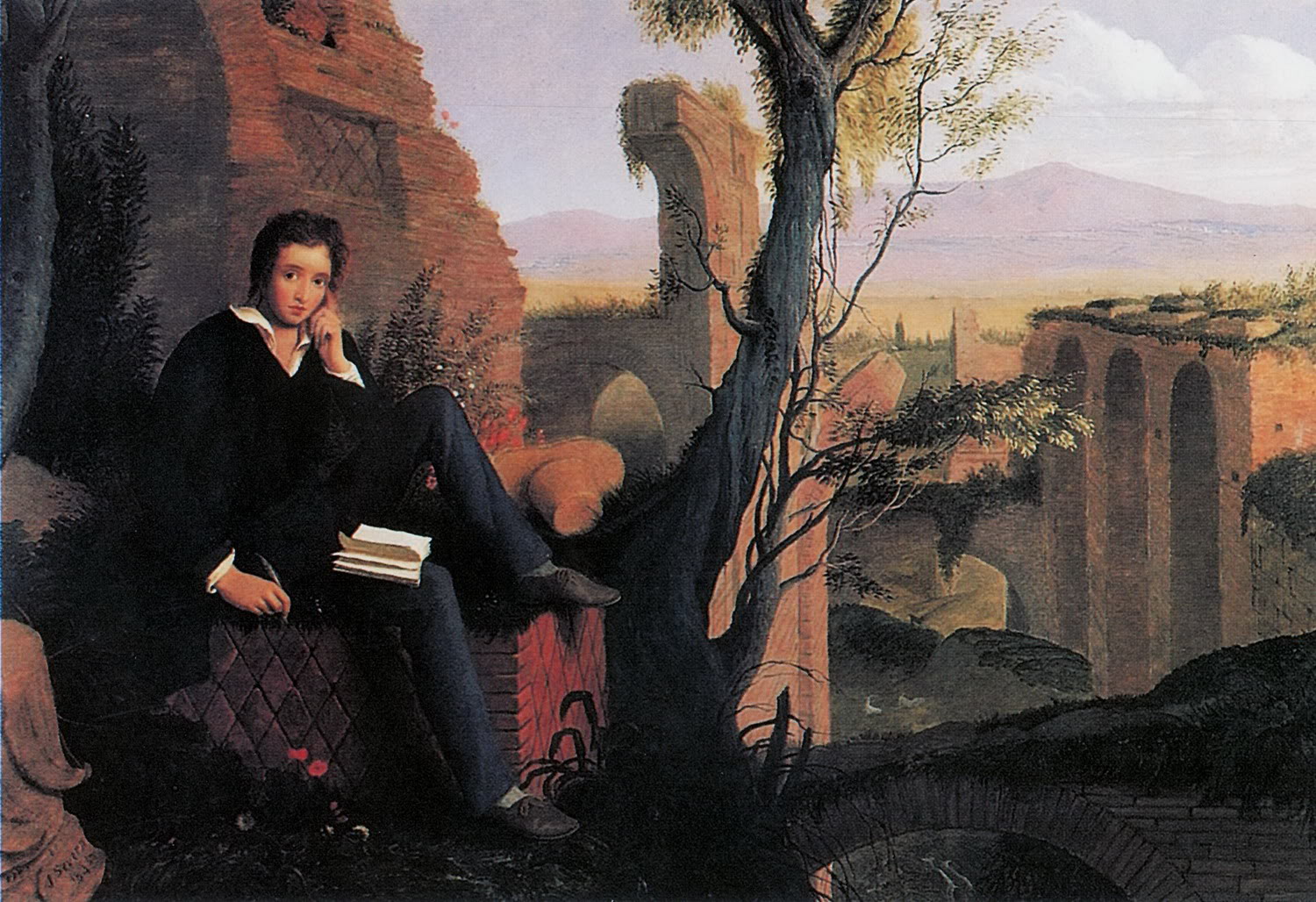

A double meaning is deployed here through the homophones morning and mourning, which taken together allude to the classic analogy between sleep and death. The poem then becomes more hallucinatory or surreal, passing into the next image through the dream logic of non sequitur, “[p]lease don’t chase the clouds, pagodas.” Still there’s cohesive symbolism packed into this densely. The dreamy image of a cloud has archetypal significance as a labile thought form, a symbol of forms that are impermanent, connected as much to a natural function of dreaming or to the imagination as it is to the concept of Mutability, as in Shelley, “[w]e are as clouds that veil the midnight moon; / How restlessly they speed and gleam and quiver, / Streaking the darkness radiantly! yet soon / Night closes round, and they are lost forever.” As an oneiric juxtaposition “clouds” and “pagodas” are as if edited together or associated through dream logic, but it’s clear there’s also already an implicit connection between the two images in their relation to the concept of impermanence. Enlightenment in the Buddhist sense derives much from learning how to stem the sufferings which arise from impermanence, understanding how to avoid clinging to that which can never endure according to the cyclical qualities of existence, as in “birth your life and death.” Not to “chase” after impermanence reflects this bit of wisdom. And yet coming from the omniscient announcing voice, “mindless” but internalized by the spectator, it’s as if the command intends to dissuade him from engaging in this more natural—one might say archaic—form of imagining, free from any technocratic policing of qualities where the “clouds” are like a functioning libido, a desiring freely or classically, that is, neither directed nor contained within the automatic, ritualistic, blasé and prerecorded control scheme of The Movie.

From this airy to solid image of the structure there is a phallic connotation that furthers the underlying dream logic of the next transition, into “her cunt gripped him like a warm, friendly hand,” carrying with that the implications of sacrilege; and causing further resonance of tensions between the sacred and profane, implicit in the ritualistic, and ceremonial function of The Movie—not to mention in the rendering automatic or blasé of a more profound, human or spiritual quality as we shall soon see. For the simile that Morrison employs here is to render sex as a handshake, making of it a routine, ritual, automatic event, precisely like The Movie—blasé, emptying of moments that are arguably profoundly spiritual their natural vigor, sapping them of their meaning or at least policing their qualities by reducing the ground of all human reproduction to a mere “cunt,” and sex to an automatic activity performed solely for the sake of “entertainment,” or as a “program” of escapism. For it’s precisely when the spectator tries to flee that he’s reeled back into the hallucination by escapism in another form, which is of course the real structure of this particular prison constructed as though by Morrison’s mythology of Lords, it subjects us to escapism that’s no real escape at all, but rather the very shape of our own cybernetic prisons. “[A]rt [used to] confuse us and [which blinds] us to our own enslavement,” The Movie is the escape that is no escape; a poison masquerading as a cure; a delusion or a “counterfeit infinity,” (Theodore Roszak) that was marketed to us wholesale not unlike a mind-expanding entheogen.

At this point, the oneiric passes into the onanistic, and we shall be left pondering the classic literary symbol of the gates of horn and ivory.

In one there’s life and function, the other artificial scarcity. Value from death. Rarity—

“You favor life / He sides with death / I straddle the fence / And my balls hurt,” (Jim Morrison)—

A subtitle of one of Morrison’s only published works within his lifetime, “The Lords,” is “Notes on Vision.”

Concentration, the last word of “The Movie,” is one which connotes both fixed attention and a density of fluid. Biological and narrative climax; the mechanistic, violent, sensuous, and horrific, all condensed into one last equivocal line.

[1] Theodore Roszak, The Making of a Counter Culture (1969)

[2] “A Profile of Jim Morrison and The Doors – On and Off Stage,” PBS’s Critique (1969)

[3] “The Movie,” The Doors, An American Prayer (1978)